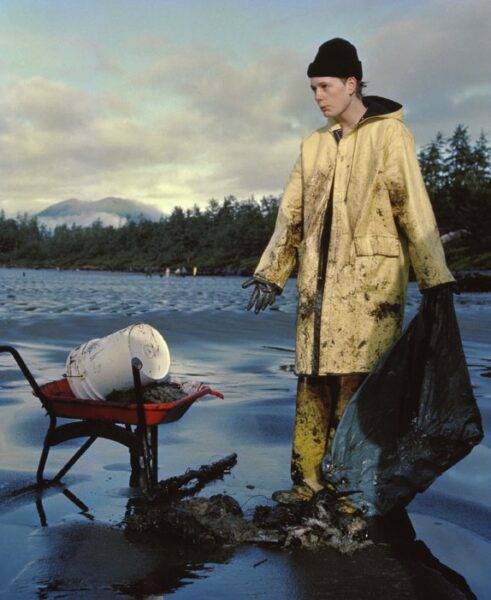

The 1989 Nestucca spill hits Long Beach

Her yellow rain gear smeared with crude oil, Valerie Langer is standing on the red carpet in the BC legislature lobby. In her gloved hand is a dead oil-soaked seabird. Flecks of oil hit the freshly painted wall as she gesticulates.

A distressed commissionaire scurries about wiping up spots of oil, while explaining that the Environment Minister is not in his office today.

It’s January 1989, just weeks after the Nestucca oil spill. During the holidays, the Nestucca oil barge rammed it’s own tugboat in Washington state after a cable snapped. The US Coast Guard ordered the leaking barge be towed out to sea. 5,500 barrels of oil were spilled. The spill could not be contained or tracked because the oil floated just below the surface. In the early days of January, to everyone’s surprise and horror, the spill began to wash ashore near Tofino.

Locals quickly mobilized the cleanup. An emergency bird hospital was established, and a kitchen was set up to feed the hundreds of volunteers who came to help.

Bureaucratic paralysis

Unfortunately the response from officials was not so quick. There were many reasons why: winter storms and huge waves, a remote and inaccessible coastline, a delay by Canadian Coast Guard in order to secure a potential payer for the cleanup, problems in information exchange between the American and Canadian authorities, duplication of efforts among agencies, and jurisdictional conflicts amongst agencies. In short, the bureaucracy was paralyzed.

Which was why Valerie and I had traveled to Victoria with our oily rain gear and a bag of dead birds—to garner media attention and to insist that the government provide personnel, equipment and money. In the end, 56,000 seabirds died. The Canadian government reported “coastal ecosystem destruction”: damage to fish stocks, marine mammals, shellfish, bald eagles and other animals that fed on oiled carcasses, as well as to native seafoods. No follow-up studies of possible long-term effects have been conducted.

Cleanup impossible

For locals it was a living nightmare. Resident Leigh Hilbert recalled, “It was very hard emotionally, to see birds dying in the oil. A lot of people reached a breaking point; they were exhausted emotionally and physically… everything was oiled, the smell was everywhere…it became our lives for weeks…”

The Nestucca spill was ‘only’ 5,500 barrels. Within months the Exxon-Valdez had spilled 257,000 barrels—almost 50 times bigger, enough to cover virtually the entire length of the BC coast. Twenty-five years later, Prince William Sound’s coastal ecosystem is permanently damaged, and thousands of gallons of toxic Exxon Valdez oil still pollute the beaches.

If Enbridge built their pipeline from the Alberta tar sands to Kitimat, 225 supertankers per year, each carrying up to 2 million barrels of diluted bitumen, would snake through the coastal archipelago and eventually travel offshore of Vancouver Island. The spectre of an oil spill 350 times the size of the Nestucca spill is not acceptable—the remote rugged coastline, and the nature of the bitumen itself, would make cleanup impossible.

One thing that hasn’t changed

Some things have changed in Clayoquot Sound since 1989. Sea otters, not seen in the Sound since the early 1900s, have returned. So have humpback whales. Eco-tourism has flourished and become the driving economic force. The area has been designated a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. There’s one thing that hasn’t changed: people around the world still feel a deep love for this place.

An oil spill in Clayoquot Sound is an unacceptable risk which makes building pipelines to the BC coast just plain wrong. Together, let’s keep Clayoquot Sound oil-free.

photo: Leigh Hilbert

Clayoquot Action campaigner Bonny Glambeck is a survivor of the Nestucca oil spill.