(This year on BC Day, in the wee hours of the morning, the tailings dam at Imperial Metals’ Mount Polley mine burst. Twenty-five million cubic metres of toxic effluent poured out into Polley Lake, and from there began to rush down Hazeltine Creek into Quesnel Lake.)

I didn’t really want to go to Mount Polley. I felt I had to go—to see for myself how bad things could get if Imperial Metals ever succeeded in opening a similar mine on Catface Mountain in Clayoquot Sound. What I saw broke my heart.

My partner Bonny & I travelled for two days from Tofino to the Yuct Ne Senxiymetkwe Camp at the mine entrance, near Likely BC.

We ran into Doug Gook, an old friend whose family has lived near Quesnel for three generations. As he described the lay of the land I began to realize that BC’s biggest mining disaster had happened in the heart of some of the province’s best wild lands.

Quesnel Lake wild

Quesnel Lake is one of the deepest lakes in the world, and home to one quarter of the Fraser River’s sockeye salmon. At the headwaters of Quesnel Lake lie the wild valleys of Cariboo Mountain Provincial Park, which connects the Bowron Lakes and Wells Gray parks.

The entire region is unceded traditional territory of the Xats’ull and other First Nations, and now home to the small community of Likely, population 350.

Polley Lake and Hazeltine Creek destroyed

We hiked in to Polley Lake, which used to be a sweet little lake with the tailings dam looming above it. I got a headache immediately, and Bonny’s sinuses began to burn, with no relief until we hiked up the hill away from Polley Lake and got back into fresh air.

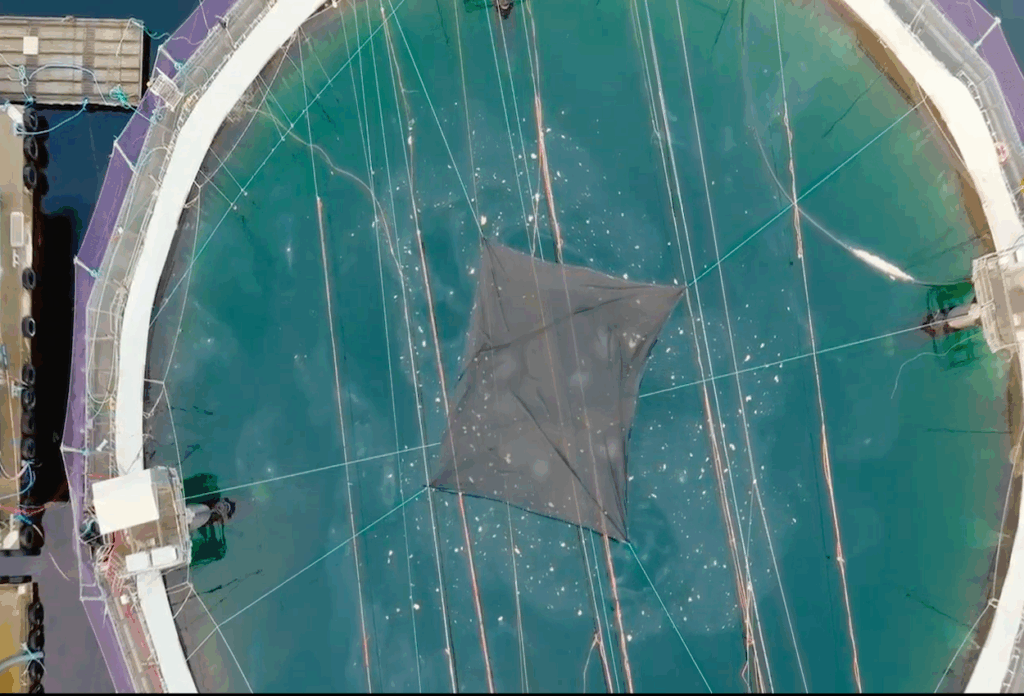

We watched fish jumping in the lake. The campsites on the shore have been closed, and Polley Lake has become a de facto tailings storage facility. We could see and hear the pumps operating, trying to lower the lake level by pumping the mine’s spilled effluent right into a natural waterway called Hazeltine Creek.

At least it used to be a natural waterway—a quiet woodland creek about two metres wide. We hiked in the next day to see what had happened there. It is still hard to think about what we witnessed. There was a fifty-metre wide swath of mine tailings with a ten-metre deep canyon running down the middle of it. A raging little creek of mine effluent was flowing through the canyon and emptying directly into Quesnel Lake. Hazeltine Creek is gone—obliterated from the face of this Earth forever.

First Nations and Likely residents left holding the bag

One of the hardest things to witness was the human impact. Locals, whether they work at the mine or not, are in shock about what has happened. Their future is completely uncertain, whether they consider the lake they love, their drinking water, their indigenous rights and title, their real estate value, or their future employment. First Nations and Likely residents bore the risks of having a mine in their backyard, and now they have been left holding the bag.

Imperial Metals had no disaster plan in place, nor have they yet made one public. They have hinted that it is not possible to clean the mess up. But no doubt if they had money leaking from their bank account they would fix that leak immediately. If the toxic plume floating around Quesnel Lake was pure gold dust, they would invent a machine if necessary to extract it from the water. This company is in the business literally of moving mountains—if they can make a buck.

Death of a lake?

As we stood on the bridge at Likely watching this year’s sockeye swimming into the lake by the dozens, I pondered the future of Quesnel Lake. Could we be witnessing the beginning of the death of a living lake? Could the lake suddenly die—or will it be a slower and more insidious passing?

The toxins will now begin to move, not just throughout Quesnel Lake and down the Fraser watershed, but also upstream in the gills of the spawning salmon, being eaten by bears, then dispersed throughout the food web. This stuff will begin to spread and it’s anybody’s guess how that will play out. Next spring this year’s sockeye eggs will hatch, and the fry will spend a year rearing in this toxic soup—what will happen to the sockeye run in 4 years, and for generations to come?

Wake-up call

The Mt Polley mine disaster must serve as a wake-up call. The BC government has to provide clean drinking water and compensation for people impacted by the spill, and Imperial Metals needs to clean up their mess. Those toxins need to be rounded up and stored safely.

Mining policy in BC needs an overhaul—some of it was written way back in the 1800’s and is out of touch with modern realities.

One good first step would be to designate mining no-go zones. Some places are too special to be put at risk by mining—places like Clayoqout Sound, or the headwaters of the world-famous Adams River sockeye run, where Imperial wants to build their Ruddock Creek mine in Secwepemc territory.

Mark the date: On Tuesday October 21, Clayoquot Action’s Dan Lewis and Bonny Glambeck will be joined by Cree/Nuu chah nulth filmaker Nitanis Desjarlais to share images and stories from their time at the Yuct Ne Senxiymetkwe Camp. Join us for an informative evening and discussion of how to make sure Imperial Metals never opens mines in Clayoquot Sound.

Dan Lewis is Executive Director of Clayoquot Action.