I never expected to end up in maximum security prison when I moved to Tofino in 1988. I had just finished my fourth season of tree planting—I knew what would happen to Clayoquot Sound’s rainforest if something didn’t change, soon. People often ask what brought me to Tofino. “My Volkswagen van,” I quip, but really it was the big trees, which I had fallen in love with as a teenager back in 1979.

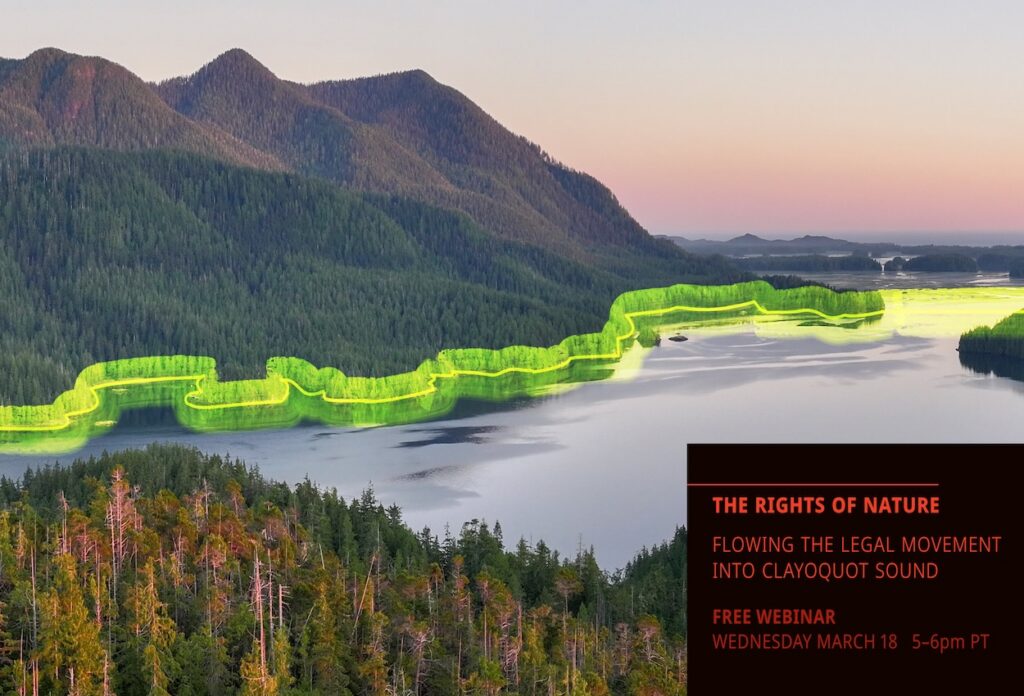

When I rolled into town, the community was in an uproar over a logging road being blasted into Ahousaht First Nations territory—along Millar Channel, heading for Sulphur Passage and onward to the Megin River valley. Brave individuals, including Ahousaht hereditary chief (the late) Earl Maquinna George, were staging a resistance at the end of the road, using peaceful and creative means to stop the road building. It was a hot buggy summer, full of life-threatening confrontations with the loggers. By September, thirty seven people had been arrested. As it turned out, the logging company did not even have road-building permits—the road was illegal!

We succeeded in stopping the road from entering Sulphur Passage. In 1993 Sulphur Pass and the Megin River valley were added to Strathcona Provincial Park. The Megin and Moyeha, along with Clayoquot Sound’s other unlogged river valleys, comprise Vancouver Island’s Last Great Rainforest. Everything outside of park boundaries is still open for logging.

Current logging in Shark Creek

Current logging in Shark Creek

I was dismayed recently to hear of logging near the borders of the Sulphur Passage park, hacking away at what remains of the ancient rainforest (photo above taken June 3rd, 2015). The logging is taking place in the headwaters of Shark Creek, so named for the sacred waterfall at its mouth—basking sharks use the pool there as a nursery.

Forests are carbon banks

Forests are carbon banks

As the western half of Canada goes up in smoke, I’ve been pondering the future of BC’s forests. A recent report from the Sierra Club BC found that in the past decade “BC forests have been releasing dramatically more carbon into the atmosphere than they have absorbed out of the atmosphere”. Campaigner Jens Wieting goes on to say “Restoring BC’s forests so that we are banking carbon rather than withdrawing it, is necessary not just for our climate but also for water quality, salmon habitat and forest jobs. If the provincial government shifts subsidies from fossil fuels to forestry and other climate solutions, we can create jobs that will reduce emissions, slow climate change, and support communities, the economy and forests, instead of putting them at risk.”

I spend a week in jail

That summer of 1988 I joined the crew on the road and committed myself to protecting Clayoquot Sound. I was arrested for peacefully preventing the drill rig from working. The judge sentenced me and 5 other women to a week in jail. He thought to make an example of us to deter others. Little did he know we were the thin edge of the wedge that would grow to become a full-fledged rainforest uprising by 1993.

Today the scar of that road to nowhere is visible on the way to Hot Springs Cove. Around the bend lies the Megin River Class A provincial park, a reminder of the power of taking a stand for Nature. It is time to stop logging Clayoquot’s rainforests, and bank them for the future.

Bonny Glambeck is Clayoquot Action’s Campaigns Director.