Auditor General Carol Bellringer issued a scathing report after completing a two-year audit of mining regulation in British Columbia, writing “Almost all of our expectations for a robust compliance and enforcement program were not met. The compliance and enforcement activities of both the Ministry of Energy and Mines, and the Ministry of Environment are not set up to protect the province from environmental risks.”

Bellringer’s report identified water contamination as the major risk to the environment from mining activities. This is especially critical in British Columbia, where water often supports populations of wild salmon. While government enforcement has been declining, the risk can only increase as lower grade ore bodies are mined, creating larger quantities of waste rock, which must be stored safely in perpetuity.

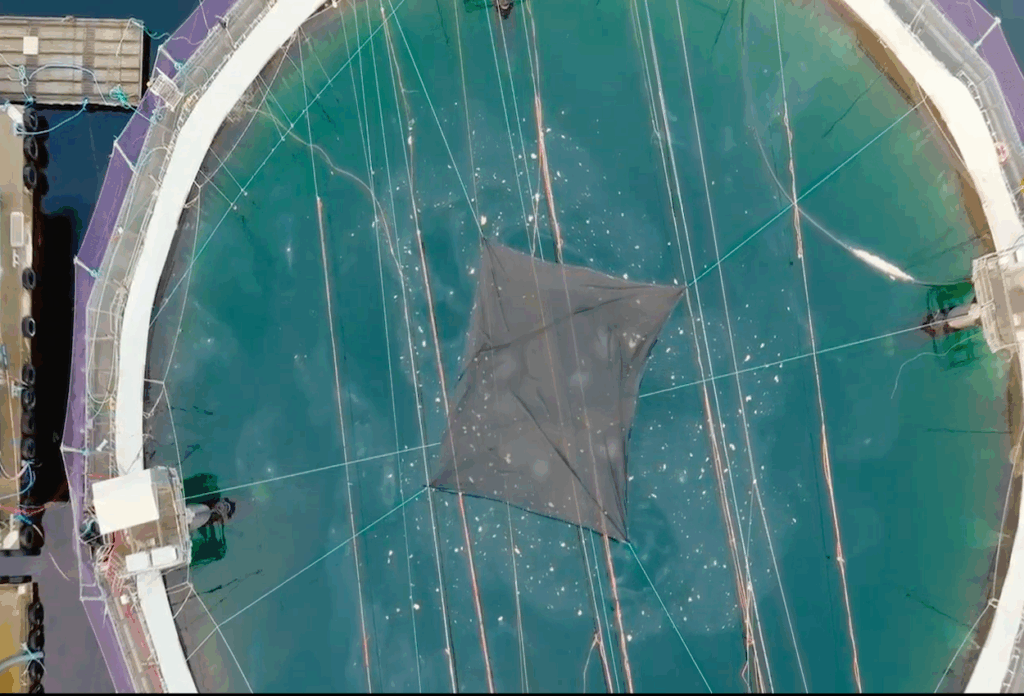

The risk is real as Imperial Metals demonstrated when the tailings dam at their Mount Polley open-pit copper mine burst, sending 25 million cubic metres of toxic slurry into Quesnel Lake, home to one quarter of the Fraser River’s sockeye salmon.

Mount Polley was preventable

An expert panel retained by the government concluded in 2015 that the Mount Polley tailings pond breached because the dam design failed to account for an unstable foundation, but the flaw was compounded over the many years that the dam was repeatedly raised to accommodate a growing lake of toxic waste.

Had the Ministry of Mines completed the required annual inspections, ministry staff would have identified that Imperial Metals was not actually building the dam to the prescribed design, and was raising the dam without any long-term planning.

Mines Minister Bill Bennett conceded last week that the “margins of risk” were “too narrow” and that Mount Polley was a disaster waiting to happen.

Who will beheld accountable?

Although Bennett said he accepts the recommendations of the Auditor General, he balked at her suggestion that the government could have prevented the Mount Polley disaster, saying the report does “create liability issues for us.”

There are multiple legal actions in the works. The company, engineers—everyone wants to put the blame somewhere else. If the auditor general is correct that Mount Polley could have been prevented by proper government oversight, then the Ministry—and thus taxpayers—could be held liable.

The AG’s report concluded that, to avoid future disasters, “business as usual cannot continue.” One way that mining in BC must change is to ban mining in locales where the risks of harm to the environment outweigh the economic benefits. With Imperial Metals considering a Mount Polley-type mine in Ahousaht First Nations territory just north of Tofino, it’s time to ban mining in the Clayoquot Sound UNESCO Biosphere Reserve forever.

Read the Auditor General’s full report here.

Check out ‘Cleaning up BC’s Dirty Mining Industry‘ from Clayoquot Action and the Wilderness Committee.

Dan Lewis is Executive Director of Clayoquot Action.