Mist rising off the lake, jagged silhouettes of remnant ancient cedars piercing the skyline as the sun clears the ridge. People milling about in the dust and gravel, waiting tensely. The rumble of approaching trucks, bright headlights coming around the bend in the road—the loggers are here. Blare of megaphone addressing the crowd of people blocking the road. Those who are not willing to risk arrest are asked to step aside, leaving one sole forest protector, the late Sue Fraser. Your classic silver-haired church lady, straight out of the 1950s, with her purse over her arm, a logging truck idling less than a metre in front of her, everyone waiting with bated breath.

This is not a scene from Fairy Creek. It happened on the Clayoquot Arm Bridge in 1992, during the War in the Woods. Today that term is often used to refer to the peak of that conflict—Clayoquot Summer 1993, which was the largest act of civil disobedience in Canadian history (until the folks at Fairy Creek broke that record). But in fact there was a long series of conflicts, stretched out over a decade or more.

It all began on Meares Island

This all arguably began in the early 80s with the conflict surrounding Meares Island near Tofino, now known as the Wah-Nah-Jus/Hilth-hoo-is Tribal Park. The Nuu-chah-nulth tribes of Tla-o-qui-aht and Ahousaht united to defend their ancestral homelands from clearcut logging by Macmillan Bloedel. This culminated in a stand-off on Meares Island at Heelboom Bay. When the loggers arrived, they were met by a crowd of hundreds, with television cameras rolling. Tla-o-qui-aht Chief Councillor Moses Martin greeted the loggers, and in traditional fashion invited them ashore for a meal, with one important caveat—“please leave your chainsaws on the boat”. The publicity campaign mounted by environmentalists and on-the-ground actions bought enough time for the Nations to win an injunction preventing any logging on Meares until a treaty is signed (thus kicking off BC’s modern-day Treaty process).

Within years, images of Haida elders in full regalia stopping logging trucks dominated the evening news, and eventually the federal and BC governments signed a deal with the Haida, creating the Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve.

By the 1980s industrial clearcut logging was reaching a furied peak. It was getting hard for anyone leaving the cities not to notice entire mountainsides covered in massive burned-out stumps from ridge to river’s edge. Meanwhile the TV news was talking about a hole in our ozone layer, and NASA had begun talking about rising temperatures due to ‘greenhouse gas’ emissions. Clearly our planet was in trouble…

As pressure mounted to protect key remaining wild areas, the government responded as they typically do, with an inquiry. That report outlined many areas with resource conflicts—in other words potential parks which were slated for resource extraction. This was translated by Valhalla Wilderness Society into an aspirational map which displayed the preservation agenda for the coming years.

Settlers mobilise

A turning point in this story occurred in 1988 when settlers, who had mobilised to support First Nations, began to use direct action to stop resource extraction. This started with the Strathcona Park mining protest, followed by the Sulphur Passage logging blockade in Clayoquot Sound. Thus began a cross-Island alliance of communities connected by Strathcona Park, which comes right to tidewater near Ahousat.

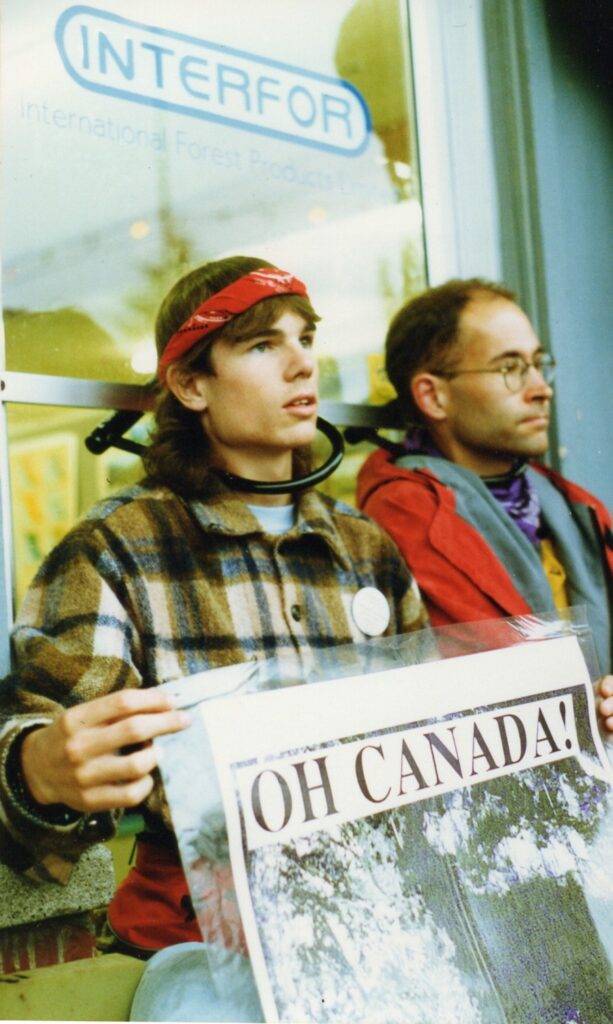

By the early 90s there was a series of blockades: the Tsitika Valley on northern Vancouver Island, the Walbran Valley near Victoria, and the Bulson Valley near Tofino. What made all of these locations unique was the presence of an intact watershed—a river valley which had never been roaded or logged—places like Fairy Creek. These were small events, but indicated that a significant amount of people were concerned enough to risk arrest in order to stop logging of ancient forests.

In September 1991 the Temperate Rainforest Action Coalition was formed on Clayoquot Island near Tofino. A large group of people circled up after a weekend-long gathering to find a way to work together to grow the movement. We were very close to forming a Tofino branch of Earth First!, but in the end agreed that peaceful civil disobedience was the way forward. This coalition became the network that coordinated support in the cities for the frontlines.

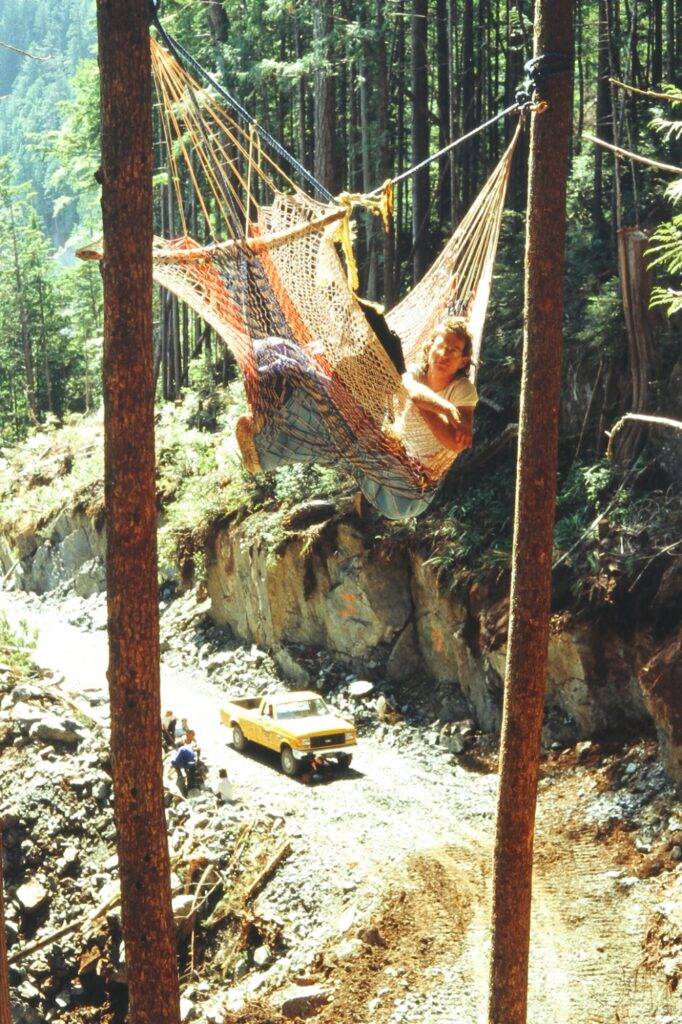

The places where these conflicts were occurring were remote and difficult to access. People were driven to do desperate things, such as hanging from cliffs in wicker chairs, hanging from hammocks in the tree-tops, and climbing up on active drilling rigs. It was clear something needed to change if the movement were to succeed…

Read Part 2 here.

Dan Lewis is Executive Director of Clayoquot Action.

Previously published in Watershed Sentinel.

Clayoquot Sound 1988. Mark Hobson photo