The call came in at the end of a busy day last week: ‘Cermaq is experiencing a mass die-off at two of their farms in Clayoquot Sound’. By early morning the next day we had assembled a volunteer boat driver and photographer, sourced a donated water taxi, and raised the funds to fuel the boat and hire a videographer complete with drone. We set off in anticipation.

The first farm we got to didn’t seem to have any unusual activity, other than the whole Herbert Inlet was a weird murky turquoise. An employee boated over to photograph us, and a polite exchange followed. ‘We’re not sure what this colour is’, he said. ‘We’ve been seeing it for six weeks—could be Chryso’ (shorthand for Chrysochromulina, a species of algae).

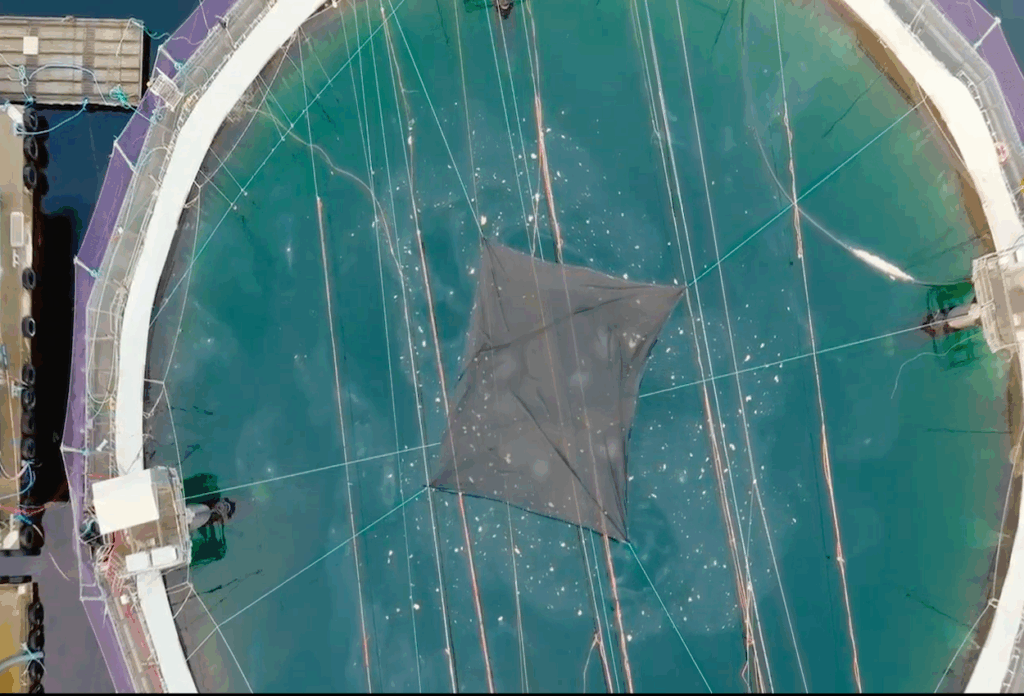

The second farm we reached was the Millar Channel farm, just kilometres north of the site evicted by Ahousaht First Nations, after it was occupied by the Yaakswiis Warriors last September. There was a hum of activity: workers tossing dead salmon into totes, which were lifted and dumped into semi-trailers designed to haul away animal remains. The tubes sucking the dead fish (morts) from the pens were getting plugged up with the sheer numbers, and divers were in the pens unplugging them.

We observed the activity, documenting what was going on and taking video and photos. A fish farm boat then followed us to the Dixon Bay farm, which appeared to be dormant. Time to head back to Tofino to get the word out!

Disease or bloom to blame?

When we had checked Cermaq’s website as we left town, there was nothing online about this. Sure enough, when we arrived in town they had posted that the die-offs began around the May long weekend, and were caused by a harmful algal bloom (HAB) called Chrysochromulina. It is possible the fish were already stressed by disease—no-one will know until a certified veterinarian reports on the cause of death.

This bloom is unusually deep—deeper than the open-net pens. This means the normal mitigation procedure of pumping oxygenated water up from the bottom of the pens won’t work—they would just be pumping more toxic algae to the surface.

When asked by CBC what the company planned to do about it, Cermaq’s spokesperson said “We are just hoping that the weather will change and maybe rain, and that would dissipate the problem”.

An incredible response, when most of British Columbia is already under water restrictions, and preparing for a summer as dry or worse than last year, when wild salmon fry were dying in rivers and wildfires raged.

Salmon farms contributing to global increase in HABs

During the past decade, there has been a worldwide increase in marine microalgae that are harmful to finfish, shellfish and humans. Cermaq has had problems with HABs since at least 2001. Most recently, Cermaq lost 25,000 kilograms of farmed salmon at a Clayoquot Sound operation in October 2015.

Toxic algal blooms associated with intensive aquaculture operations have been recorded around the world. A major algal bloom devastated the Chilean salmon farming industry earlier this year, also killing massive amounts of sea life, causing economic hardship for inshore fishermen, and throwing the island of Chiloe into civic unrest.

It is well known that agricultural run-off increases the occurrence of HABs, due to increased nutrient loading. Unlike other feedlots, salmon farms deposit their agricultural waste directly into the oceans—many tonnes of salmon feces daily. In effect they are using the ocean as an open sewer.

Surrounding marine life also affected

Die-offs at salmon farms are not good for anybody—not the workers cleaning up the mess, the fish that are suffocating in the bloom, the rest of the fish suffering in the pens, or marine life in the surrounding environment. This HAB could negatively affect wild salmon smolts, and other creatures that live in shallow inshore waters, as well as any animal which cannot move, such as clams.

With all the negative impacts of industrial salmon farming, it’s time to legislate the removal salmon farms from the ocean into closed containment, so they can treat their sewage rather than pumping it directly into the ocean.

Dan Lewis is Executive Director of Clayoquot Action.