The Nuu chah nulth First Nations have an expression, “hishuk-ish tsawalk: everything is one, everything is connected”. Few things illustrate this better than wild salmon. Salmon begin their lives as eggs in cool freshwater streams. The hatchlings make their way down to the sea, where they spend time rearing. (Yes, you do score points for knowing that some species rear in freshwater for a winter or two before migrating out). When they are big enough, they head off on a vast oceanic voyage. After 3-5 years, the fish return home—somehow, right back to the very stream where they hatched!

Everybody is waiting when the salmon runs return: bears, wolves, eagles, otters, even songbirds. There are over one hundred wildlife species which depend on healthy runs of wild salmon in order to fatten up for the long, wet winters.

We are all Salmon People

Not to mention people. Salmon have been an integral part of First Nations cultures on the West Coast (and way up into the Interior, as far as Prince George and beyond) for millennia. The abundance of protein helped create a culture rich with art, celebrations, oral literature and theatre. Salmon have also been a key part of settler culture here too—we are all Salmon People now.

And then there’s the trees. Coastal rainforests produce cedar, spruce and hemlocks of massive proportions—some close to 100 metres tall. There are living giants growing in Clayoquot Sound which sprouted during the time of the Roman Empire. But coastal soils are very shallow, and nutrient poor.

So how do the trees grow so big? Turns out that wild salmon bring back marine nutrients, including the nitrogen missing in the earth here. So salmon feed not only people and wildlife, but trees as well.

Sadly, it is now Code Red for wild salmon

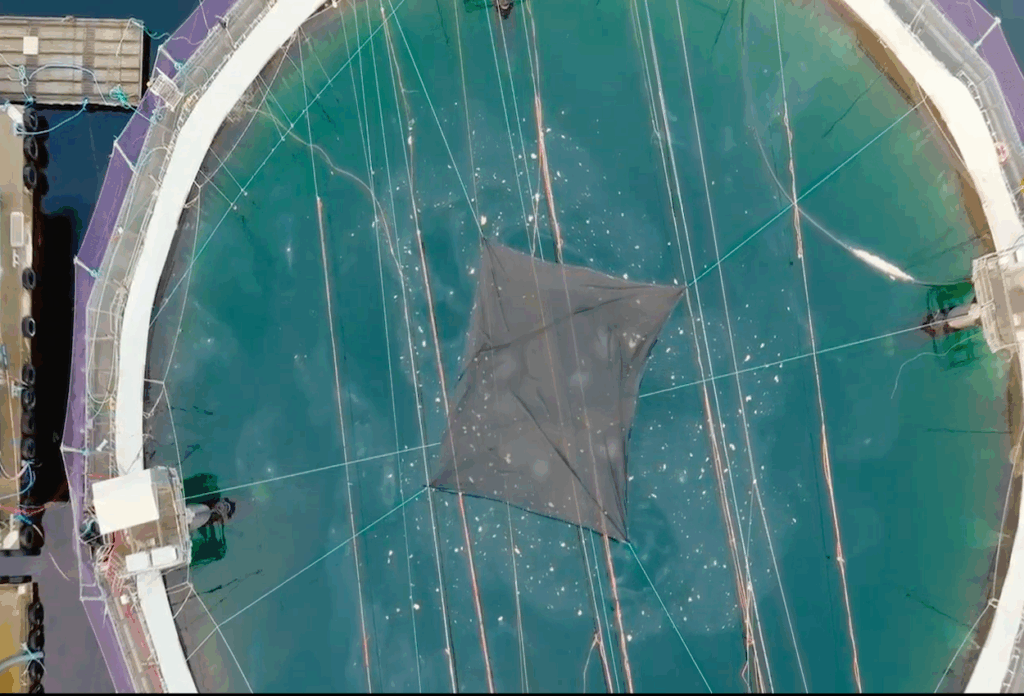

Sadly, it is now Code Red for wild salmon. Their biggest challenge is early marine survival. What could be the problem? Tiny juveniles and returning adults are forced to run a gauntlet of crowded factory fish farms situated along wild salmon migration corridors. And open-net pens do nothing to prevent pathogens, parasites, and pollution from spreading to wild salmon.

The evidence is overwhelming that this entire intricate ecosystem is being put at risk by international salmon farming companies. First Nations are unable to collect food fish to feed their families. Their freezers are empty, and the abundance is missed. This creates great hardship, especially as food prices continue to soar…

Salmon face many threats including the climate crisis. But unlike the climate crisis, which will require international cooperation, salmon farming is entirely within our ability to control. And Canada’s federal government has committed to removing fish farms from BC waters by 2025.

Doing so will allow wild salmon to flourish again, and begin to rebuild to their former abundance. Nature knows how to take care of herself, if we humans could simply stop messing things up and let the magic happen!

Dan Lewis is Executive Director of Clayoquot Action.